Posted 2022 July 28

After co-presenting with Graham Pugh at MacAdmins Campfire Sessions, I checked in with a colleague at work. We are in the midst of setting up AutoPkg as a central service and I wanted to make certain that the description of my current setup was clear to him, since much of that setup will be transferred over to the new service (and he will be doing a lot of the work). Near the end of our text-based conversation, I mentioned that, “I was pleased with comments in the #psumac Slack channel that said that people wanted to watch it again or wanted to explore more about [topics mentioned].” He replied, “Yeah, I think it’s pretty cool how you’ve established yourself as an expert.” That comment took me aback. I knew it was offered from a place of generosity, but it took me a while for me to process it.

As someone who has been very active in the international Mac admins community for about a decade, I acknowledge that I have a “profile” (you probably wouldn’t be reading this post if I didn’t). Having a profile, however, doesn’t make me an expert. In fact, who is ever an “expert”? I prefer to focus on expertise, which we all have. That is when a person’s base of knowledge is combined with very specific work or research. Don’t believe me? Let me share some personal anecdotes that might lead you to realize that you too have developed expertise that is worth sharing and that the bar is lower than one might think to do that.

Research Isn’t Always Big

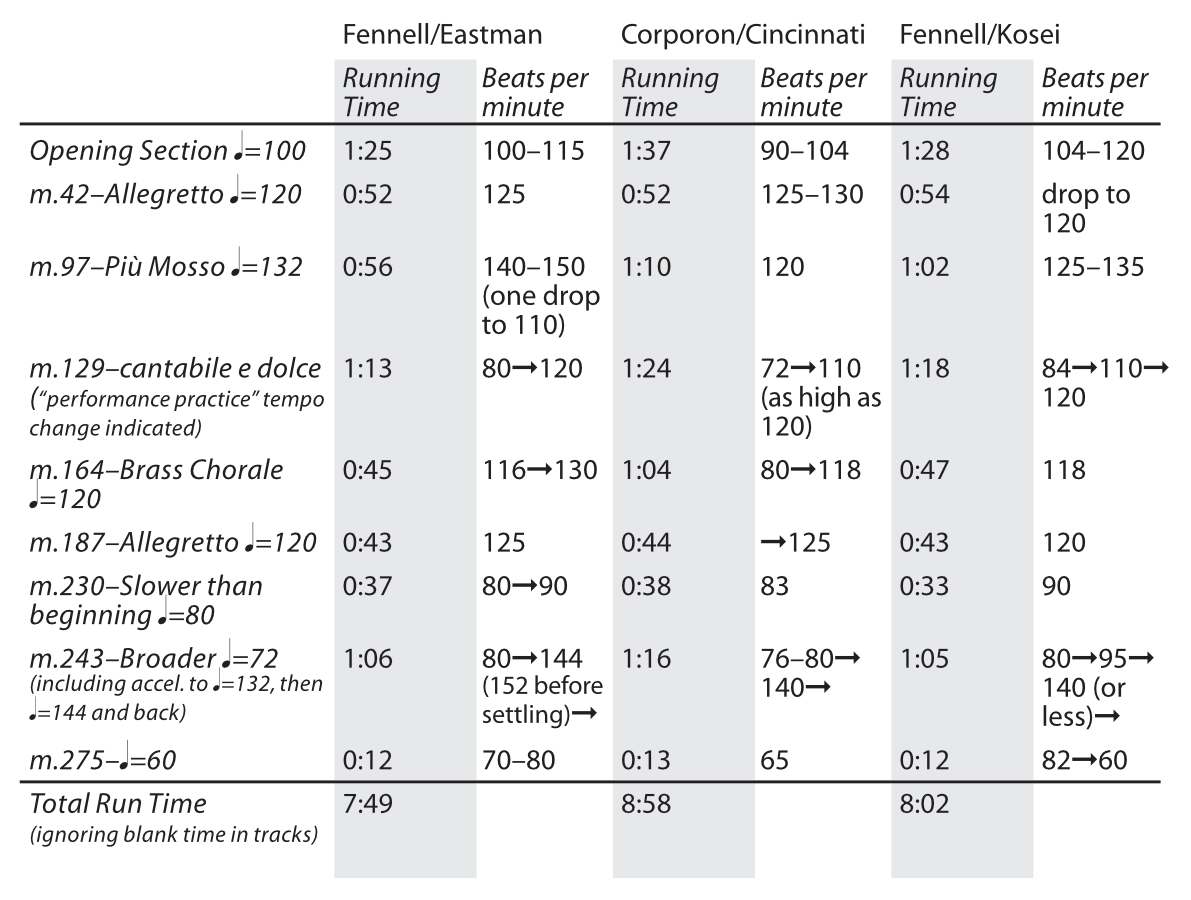

As a part of my Masters degree in Music, I participated in a three-week summer conducting workshop on two occasions. Participants had to write a weekly 5-page paper in addition to all the practical work related to conducting. For one of the papers, I compared three recordings of the same piece of symphonic band music and broke down the differences in tempo (pictured at right), tone colour, and articulation.

I got an A on that paper from a guest professor, who remarked that its contents were “very valuable” and wondered aloud if it might be accepted for publication by The Instrumentalist, a respected band music education magazine. Wait, what now? I could be published? This was a surprise to me. I had done some short-but-intense work on a very specific topic that either no one else had bothered to do or no one else had documented. Was I an expert on this particular composition? No. Was there something people could learn from my research? Apparently. After some rewriting to match the style of a magazine article and incorporating other feedback, I did get this article published (albeit a few years later and in a different publication), but that was my first inkling that you didn’t need to be an expert on all things to share what you learned. “Research” doesn’t have to be a big, long-term project; blogging platforms eliminate most of the gatekeeping and make the size almost irrelevant. Your topic can be something narrow and deep (or wide and shallow)—it just has to have value. And don’t be surprised if someone has to tell you that you should share it before you realize its value.

Presenting About a Recent Project

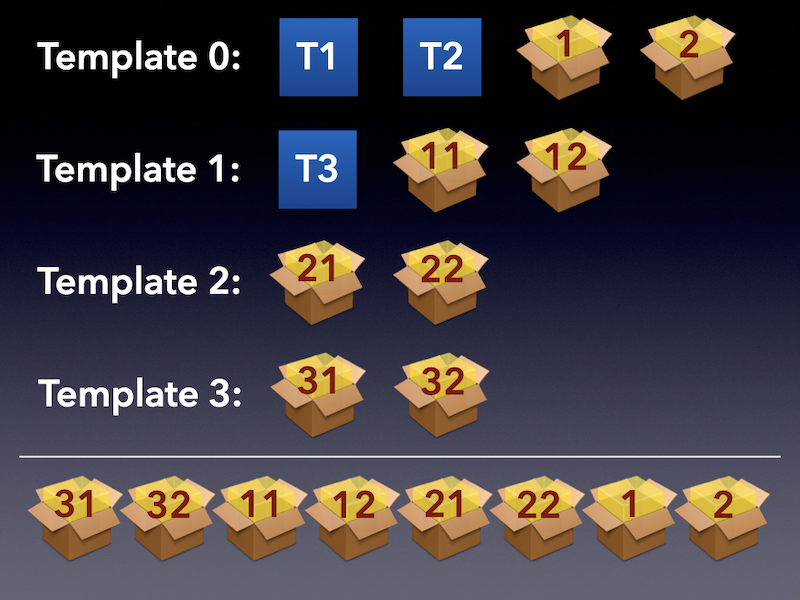

I trained as a teacher, so giving presentations at Mac admin conferences has proved to be a good way for me to give back to the community. (It also ended up being the main way to get funded to go to conferences, since eliminating the registration fee brought costs down a lot.) I got the opportunity to speak at the 2014 MacAdmins Conference at Penn State on the topic of modular image creation, the last half of which focussed on AutoDMG by Per Olafsson. I had moved from InstaDMG to AutoDMG for image creation and was not yet using a “thin image” or “no image” methodology. I was creating a 60+ GB deployment image that always started with a disk image built from scratch by AutoDMG, so I fully leveraged its templating system much like I did in InstaDMG. While AutoDMG supported this workflow, most people didn’t need to leverage the depth of features available like I did to make that tool do what they wanted.

In preparing the talk, I dug a little more into the various combinations of how nested templates worked and the exact order that AutoDMG would install the packages depending on how the templates were nested. This type of incidental research is a common occurrence when preparing any talk: the work I have already done provides the bulk of the content, but as I build a specific slide or section, I will think of an edge case that I haven’t fully tested. Because I want to provide accurate information, I will dig that extra bit deeper to see how that edge case resolves. So not only does preparing a presentation help me document what I have learned, I often learn even more about the tool I’m working with. More often than not, it also leads me to ask questions of the developer of an Open Source tool and sometimes even surface a bug or two. My expertise grows through this process.

In the case of that 2014 presentation, imagine my surprise when Per reached out to me afterwards and asked if he could link to the video on the AutoDMG GitHub project page. I was honoured. The request didn’t come because I am an expert—clearly, the person who wrote the code knows more than me. What I created just had to be useful. That presentation is still the most viewed presentation I have ever given because of this exposure.

Maybe presenting isn’t your thing (although I’d still recommend giving it a try, even just within your work site or meetup group). Good documentation and technical writing can provide the same benefits, both for you and for the community. The people writing the code are often busy writing the code, so creating a talk or an informative article can be a great way to give back in thanks for to projects that make your work easier.

Don’t Be Intimidated

One thing that gets in the way of people sharing what they’ve learned is thinking that a certain stage or arena is too big for them. For example, “I could never present at Conference X; I’m a nobody.” From experience, I can tell you that things look a lot different from backstage. For 5 years, I was the game clock operator for the Calgary 88s of the World Basketball League, a professional summer league. The team played their games out of the Olympic Saddledome, the venue that had hosted Hockey and Figure Skating for the 1988 Olympic Winter Games and was/is the home to the NHL’s Calgary Flames. For someone who was raised with a great interest in sport, it was a bit surreal entering the Saddledome via the Player’s Entrance, walking though parts of the arena rarely traversed by the public, and then arriving at the place on the floor just inside the hockey boards where I would do my work.

It didn’t take long, however, for that mystique to fade away. I quickly realized that it was just a building, that the players and coaches were just trying to earn a living, and that the work I was doing was only different from what I had done in University and High School in that more people saw my work on a bigger canvas (including my errors). Yes, the technical hardware was better than what I was used to and there was a little more pressure because this was not amateur sport, but the foundational skills I had built served me well in this new job. I was also part of a supportive team that made things easier because we were all experiencing this together. Taking the mystique out of the situation made it much easier to perform at a high level.

There are all sorts of things that each of us perceive to be larger than life. My experience is that these are self-created barriers. Once you get into the work, things become right-sized. This is not to negate the fact that you might encounter barriers that are not of your own making or that you cannot overcome on your own, but if you can get over that initial intimidation factor, you will often find rewards on the other side.

You Can Too!

I started this post by mentioning how I balked at the word “expert.” In all the stories I shared above, I had already established a base of knowledge: having an undergraduate music degree, having worked with modular imaging for a few years, being a basketball minor official. If you think about academic institutions, the higher the degree, the more specialized you get. As a Mac admin, you already have a base of knowledge (which will vary depending on how you got here)—think of that as your undergraduate degree. Circumstances will often dictate that you need to dig deeper into something to get a job done—more like Masters work. Those hard-fought learnings are often great fodder for internal documentation, blog posts, talks at a meetup or conference, or other methods of sharing (like responding to questions on the MacAdmins Slack). My recent adoption of JamfUploader for all my production AutoPkg recipes gave me plenty of fodder for my presentation with Graham as well as some future blog posts.

Don’t be intimidated because you don’t think you are good enough or because the topic is not that important. At the very worst, documenting what you’ve learned will be of benefit to Future You or a colleague. The process itself provides benefits. And the more you do it, the better you get at it. This blog didn’t even exist until Vaughn Miller and I did a workshop on Sharing What We’ve Learned in 2017, which made me take a deep dive into setting up a blogging platform. Now, it has become an essential way for me to give back to the community that has given so much to me.

You don’t have to shoot for the stars when you start. Start simple. Because you have expertise to share!